…………to be led by a focus on manufacturing

Global Manufacturing

Landscape Global Manufacturing was significantly impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic, both during (various lockdowns imposed) and after (supply chain issues). While some industries fared far worse than others, most sectors suffered major disruption. Whilst during the initial phases of lockdown the ecosystem was impacted by lack of mobility and a massive shutdown of demand, the more long-lasting effect has been disruptions to supply chains from inputs to the manufacturing process (raw materials/finished goods) as well as labour force attrition.

Pre COVID-19

Over the 30-year period from the mid 80’s to 2012, China’s has been dominant when it came to manufacturing. Their rise to a manufacturing powerhouse was primarily driven by their large population, allowing for structurally lower labour costs, which led to efficient and economic production for the rest of the world and their eventual status as a manufacturing hub. As a result, China now holds a significant technological advantage over its global manufacturing peers, holding 28% market share pre-COVID19

However, the trend of de-globalisation from 2015 onwards and accelerated by the Trump Government started to questions China’s dominance of global supply chains. Other geographies also started to become wary of its territorial ambitions and influence on technology and R&D. The China + 1 thematic was already in play and accelerated by onset of COVID-19.

Post COVID-19

China has faced significant headwinds since the pandemic. Its economy has slowed dramatically due to its troubled property sector as well its government’s zero tolerance policy for COVID infections. Essentially the economy has been largely shut down for a few years now. The rest of the world placed a significant reliance on China due to their capability to produce goods at a cheaper price due to their structural advantages and scale. As a result, corporates around the world have been focused on diversifying risks associated to their supply chain and an “over-reliance” on China.

Where to from here…

China was essentially “exporting deflation” to the rest of the world. However, with supply-side shortages and rising demand post lockdowns, inflationary conditions have persisted. Other economies like India, Vietnam and Indonesia for example have the potential to take advantage of global supply chain diversification. India has the advantage of a significant labour force in skilled areas. However, it is the unskilled areas i.e. labour-intensive manufacturing where progress needs to occur.

India Manufacturing: 1990 – 2020

India vs China – manufacturing vs services – two different paths

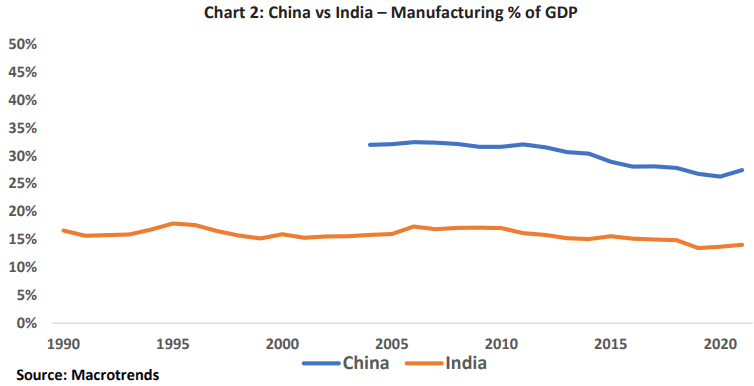

While both India and China have been the growth economies of the last 30 years, their growth has been quite divergent as China chose manufacturing as the growth engine of its economy, by leveraging its large and low-cost labour force. Whilst China’s manufacturing data is not readily available prior to 2004, it contributed between 30-40% of its GDP, whilst India which progressed more through an internal demand for services driven route, contributed only 15-20% of its GDP through manufacturing.

China’s focus on manufacturing

One of the key benefits from focusing upon manufacturing is the job opportunities that arise from it. China’s overwhelming supply of labour was met by the government providing opportunities through the constructions of roads, buildings and more. This significant employment was incredibly positive for the workforce and resulted in mass urbanisation across China. This increase in demand for labour met the supply and ultimately allowed for China’s workforce to be fully harnessed to its potential.

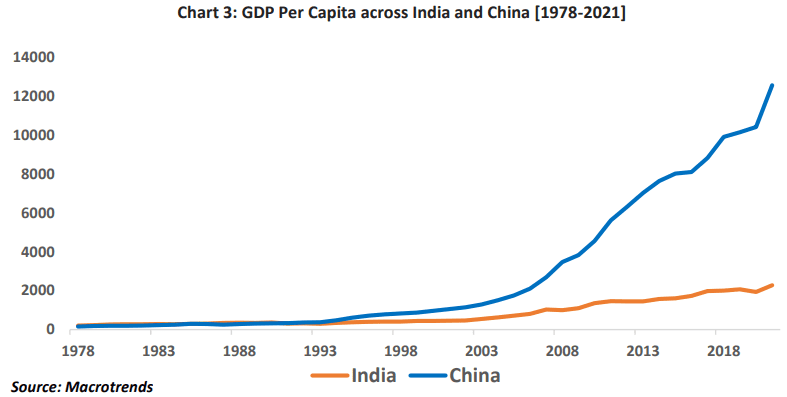

India and China’s GDP per Capita were following a largely similar trend until the 1990s. This can be attested to China’s willingness to adopt an Open-Door outlook, allowing foreign investors and companies to utilise their lower labour costs to benefit themselves. In this time, India maintained a focus upon Services leading to them falling behind in GDP-per-capita, as manufacturing has a far higher multiplier effect on GDP growth in comparison to services.

India’s weak manufacturing

India’s manufacturing as a percentage of GDP fell below 14% recently due to a lack of focus and private investment over the last decade in the lead-up to COVID-19. India had structural issues such as bureaucratic red tape, archaic labour laws, high cost of manufacturing especially due to high power and energy costs, high cost of capital (high interest rates), high corporate tax rates, inverted duties on raw material in certain cases and the inability to build scale. Additionally, infrastructure and transportation systems have been a bottleneck in the past, which is being addressed through various measures taken by the Government.

The Government’s goal is to increase manufacturing as a percentage of GDP from 15% to 25% by 2030. The initial goal set in 2014, when the Modi-led BJP came into power was 25% of GDP by 2022, which has not been achieved. The Make-in-India campaign set up in 2015 to promote manufacturing in India, with the aim of creating jobs and skilling labour, has not been successful to date.

The reality is that the manufacturing industry in India has been losing jobs since early 2016. The sector has fallen from employing 51 million to 27 million people. COVID-19 is not the only aspect contributing to this lack of employment opportunity. India’s manufacturing push to date has been in capital intensive industries. However, with close to 10 million people being added to the workforce every year, the focus has to also include labour intensive industries and be inclusive of unskilled labour. For India to boost itself into a manufacturing and economic powerhouse, these issues need to be solved sooner rather than later.

Among India’s major economic sectors, it is manufacturing which requires the highest amount of fixed investment upfront, relative to potential output (compared to agriculture and services). For investors and entrepreneurs, this presents itself as a huge risk as a huge amount of money must be committed without any guarantee of return. This has resulted in a lower presence of manufacturing industries and therefore employment opportunities.

The trouble essentially lies with government policies neglecting labour-intensive industries, which hold a distinct advantage of creating more jobs. Policies such as Make in India and Production-Linked Incentive schemes need to increasingly accommodate for this, rather than purely aiming investment towards more capital-intensive industries. However, one point to note is that labour intensive industries in the past have found it difficult to attract and retain unskilled labour. Besides there are inefficiencies and labour union related issues in unskilled labour-intensive industries hence many companies in India have switched to automation in most areas of their operation.

Government Initiatives to promote Manufacturing

Foreign Investment Rising

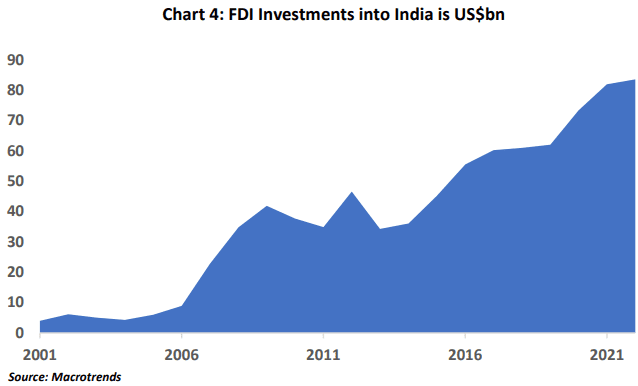

Moreover, total FDI inflow grew by 81%, i.e. from $289bn in 2007-14 to $523bn in 2015-22, indicating that the Modi

Government have been more active in accessing foreign capital given significant economic, regulatory and market

reform which is increasing making India an attractive region for foreign investment. In FY22 the industries where FDI

was directed include Computer Software & Hardware (25%), Services Sector (Fin., Banking, Insurance, NonFin/Business, Outsourcing, R&D, Courier, Tech. Testing and Analysis, Other (12%), Automobile Industry (12%), Trading 8% and Construction (Infrastructure) Activities (6%). FDI Equity inflow in Manufacturing Sectors have

increased by 76% in FY 2021-22 ($21bn) compared to previous FY 2020-21 ($12bn).

India’s FDI is set to grow for the years to come. With the current government initiative and direction, India can potentially become a global manufacturing hub2 . All these factors together may help India attract FDI worth US$ 120-160bn per year by 2025.

India evolving into a potential manufacturing hub

Table 2 – Example of Foreign Companies establishing a manufacturing capability in India.

- Construction of a steel and cement plant for $13.5bn by ArcelorMittal Nippon Steel

- A new car manufacturing facility by Suzuki Motor for $2.4bn

As described above, India has already established itself as a globally dominant manufacturer for vaccines. Additionally, in newer industries with the current gaps between global demand and supply i.e. EV’s and Electronics, India has the potential to bridge gaps by manufacturing/supply of labour. Also to note is that of the research and development (R&D) investment in developing economies, India captures almost half of all projects.

The FDI in the critical renewables sector is also becoming increasing significant. In FY22 this increased by 100% from the prior year to US$1.6bn. US$11bn has been invested in this sector over the last 12 years and there is no cap on foreign investment levels. The sector is becoming increasingly attractive due the Government’s increased support and improving economics. With India committing to being a net zero economy by 2070, investment in this sector can generate significant economic impact.

Overall an improving landscape such as lower taxes, a better regulatory environment and PLI scheme are some of the key reasons for India’s growth in manufacturing, providing incentives for foreign companies to invest in India.

Exports to be US$1tn by 2030

The Government of India has set a target of one trillion US dollars in exports by 20306 . This would mean that India would hold 5% of global total trade and be on the way to becoming an export powerhouse and that some of the government initiatives are paying off.

India’s Growth Story via its Equity Market

India should experience rising GDP per capita

China achieved a significant boost to GDP and GDP-per-capita through its focus on manufacturing. This was driven by its significant population and structural lower labour cost over a 20-year period from 1990-2010. After GDP was at similar levels in the mid-80s, India’s GDP as of 2021 is where China was in 2007. As China’s population became highly productive, its GDP per capita started to grow from rising wealth through being the supply chain to the rest of the world. However, as China’s population ages and its structural labour cost advantage dissipates, it now must focus on consumption and an internally focused strategy – hence we are seeing the emerging of the thematic of deglobalisation.

India GDP-per capita is 15 years behind China and its likely to play catch up over the next two decades as its GDP grows more from productivity and efficiency rather that population growth. India’s advantage will be in services where it has spent decades build an IT infrastructure and is set to be the hub for data storage, knowledge and warehousing (given the low cost of data and skill base it has built). However, manufacturing is critical in job creation, particularly for unskilled labour. With 10 million people entering the workforce every year the need of the hour is to promote Make in India to reduce imports and build export capability in manufacturing and take a place in global supply chains.

India’s GDP-per-capita is set to increase, which will in turn lead to higher levels of disposable income. With Indian households often saving majority of their salaries, higher levels of income will allow them to indulge themselves and purchase luxuries in the form of domestic manufactured goods. This will in turn, lead to further demand which will lead to greater growth in job opportunities. The productivity loop of an economy!

GDP Growth and correlation to markets

However, in India’s case the opposite is true. Whilst GDP growth has been strong, it is circumspect relatively to what China has achieved. However, stock market investors have enjoyed far greater returns from India than experienced in China. The scales have been kept the same on both charts. Over the last 30 years the Indian indices have been far less influenced by State owned enterprises and private enterprise has driven markets.

This is an interesting point to note for investors in Emerging Markets, Asia type broader mandates with significant weighting to China. Whilst the MSCI China has far more weight to private enterprises than it used to, the Chinese Government showed their hand in 2021 by restricting some of the progress of private enterprise. However, India is looking for leadership from private enterprise to invest in infrastructure, manufacturing and technology to give it the edge it needs.

These stocks account for 30% of the weight of the portfolio and are typically not owned by our peer India focused Fund’s / ETF’s in Australia, which tend to focus more on benchmark awareness and therefore Index heavyweights. Today, these heavyweights are predominantly Financials, Technology and Consumer stocks (60% of the Index). To us it makes sense to incorporate India’s increasing manufacturing prowess into portfolios which seek to benefit from India’s growth over the 2020’s.

Concluding Remarks

In order for India to achieve their full potential, they must follow in the footsteps of China, modelling themselves to take full advantage of their wide labour force. As China once opened their country to the FDI available to them, India too must encourage foreign companies to invest through the use of incentives and tax cuts.

As of now, China is only 15 years ahead of India in terms of GDP Per-Capita, but due to the fast-growing nature of India’s economy, it may be able to reduce this gap even more. China’s GDP Growth has recently begun to slow down after a long period of high growth, while India’s growth trend has just begun. Furthermore, along with India’s younger population entering the workforce, India is lined up to begin its climb towards the top.

China’s economy was built off the basis of demand for labour rather than the demand for goods. This is a key reason why India has fallen behind by a significant margin. But as India’s population begins to participate further in the economy, the demand for goods and services will similarly begin to grow.

Since India’s growth spurt is coming much later than China, India has to adopt its technology and services to the digital age. By providing greater online infrastructure to the country, India can lead itself to an efficient and sustainable digital future for everyone.

Our Disclaimer:

Equity Trustees Limited (“Equity Trustees”) (ABN 46 004 031 298), AFSL 240975, is the Responsible Entity for the India Avenue Equity Fund (“the Fund”). Equity Trustees is a subsidiary of EQT Holdings Limited (ABN 22 607 797 615), a publicly listed company on the Australian Securities Exchange (ASX: EQT). The Investment Manager for the Fund is India Avenue Investment Management Australia Pty. Ltd. (“IAIM”) (ABN 38 604 095 954), AFSL 478233. This publication has been prepared by IAIM to provide you with general information only. In preparing this information, we did not take into account the investment objectives,

financial situation or particular needs of any particular person. It is not intended to take the place of professional advice and you should not take action on specific issues in reliance on this information. Neither Equity Trustees, IAIM nor any of their related parties, their employees, or directors, provide any warranty of accuracy or reliability in relation to such information or accept any liability to any person who relies on it. Past performance should not be taken as an indicator of future performance. You should obtain a copy of the Product Disclosure Statement before making a decision about whether to invest in this produc